Op-Ed: Protecting the Nueces, a lesson of love and legacy

Sky Jones Lewey | Texas Hill Country Conservation Network Contributor

Fighting to protect water quality in Texas Hill Country waterways is nothing new. I had the privilege to watch, learn from, and help my parents back in the early 1980s as they raised awareness and organized opposition to keep wastewater out of the Nueces River.

It all had to do with a proposed wastewater treatment plant in Camp Wood, located in the headwater region of the Nueces, the river we lived on. At the time, it was the Texas Water Commission, now TCEQ, that permitted a wastewater treatment operation without fully considering the voices in opposition, led by Elmo Jones, my father. Dad was an excellent community organizer before that was even a thing. As a fluent Spanish speaker, he raised awareness of potential pollution on the Nueces River to all audiences. The resulting outcry was loud, targeted and unrelenting.

I still have my mother’s handwritten letters to the editor from that time. Her passion is evident in words so familiar. In 1982 Marge Jones wrote, “The Nueces River is one of the few rivers in Texas yet unpolluted – I love this river along with thousands of Texans – a river where you can get off your horse, take a handful of watercress for an energy snack and get a cool clean drink of water – a river where children can play and swim and even swallow the water without ill effects.”

Ultimately, the people in and downstream of Camp Wood prevailed. The wastewater operation plans were changed, and the treated water was designated for irrigation, a beneficial use in a dry landscape. I received a powerful first-hand lesson in how to protect my river.

In the last forty years we have avoided five wastewater discharge permits in the entire upper Nueces basin, about 4,000 square miles, which remains the largest wastewater-free headwater basin in Texas. This headwaters region contains five of the remaining pristine stream segments in the state of Texas. People and their neighbors are still fighting to protect them.

The term “pristine stream” has become the battle cry for a growing number of landowners and river lovers, like my family, who see and understand the precious and precarious nature of our state’s cleanest natural waters. Margo Denke Griffin, leader of the Friends of Hondo Canyon recently described this new cadre of water warriors in the San Antonio Express news as “a motley crew of engaged, informed, and committed Texans—ranchers, fixed-income retirees, landowners, small business owners, visitors, cedar-choppers, tree-huggers, hunters, birdwatchers, paddlers, fishermen, Republicans, Democrats, and Independents—who came together in 2018 to prevent one pristine stream from being polluted by the discharge of wastewater effluent. And now we’re fighting for 22 others.”

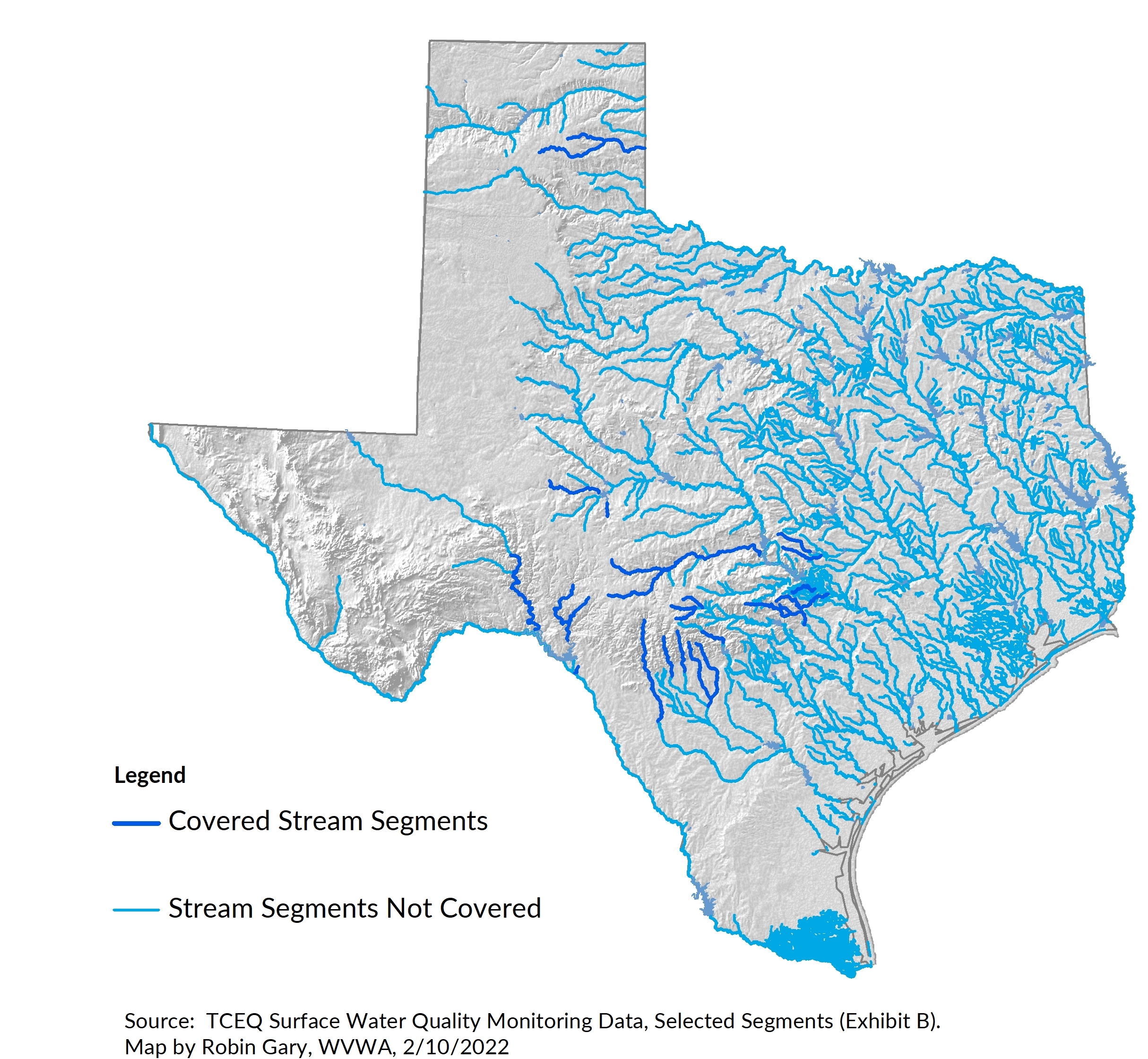

As the recent State of the Hill Country report from the Texas Hill Country Conservation Network points out, there are almost 200,000 river miles in Texas, but only a little over a thousand miles within 22 classified stream segments remain under the designation of ‘pristine’. These waterways deserve special care because they naturally carry very low levels of phosphorous—an amount of total phosphorous below detectable levels (.06 mg/l) found in 90 percent of all samples taken in the last ten years of monitoring by the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ). This data is certified, stored and publicly available in the agency’s official Surface Water Quality Monitoring (SWQM) database.

The addition of even highly treated domestic wastewater effluent carries levels of phosphorous and other nutrients that far exceed the natural levels found in these Texas streams. Sadly, experience has taught us that discharge of wastewater into pristine streams will most certainly degrade the water quality and destroy the delicate balance of the ecosystem. These waterways are so pure that even a bottle of Evian does not compare in quality.

In the last three legislative sessions, the champion for pristine streams has been Chairman Tracy King, state representative from House District 80. He introduced and guided bills to keep wastewater out of pristine streams with exceptional prowess and deft, where the issue gained strong bipartisan support, though ultimately the bills failed to pass into law.

In January this year, a coalition of individuals and organizations filed a petition requesting TCEQ to promulgate a new rule prohibiting wastewater discharge into the 22 scientifically identified pristine stream segments. The petition was supported by more than 1,300 public comments through TCEQ’s online platform.

TCEQ Commissioners held a public hearing on March 30th to discuss and act upon the petition. Unfortunately, the Governor-appointed Commissioners rejected the petition request on a 2-to-1 vote, though they instructed TCEQ staff to explore alternative options through stakeholder engagement.

Maybe something will come of it. TCEQ Commissioners still need to hear from the many Texans who want to keep some of Texas’ most beloved river places pristine—such places as the aqua blue Devils River, many cypress-lined Hill Country rivers like the Blanco, Frio and Nueces, and Barton, Hondo and Onion Creeks, among others.

The population of Texas continues to boom; we hear about it daily. Most people don’t think about the accompanying surge in the volume of wastewater that will come too and must be managed. Those of us who’ve been working to protect rivers for years most definitely think about that problem.

Now is the time for action to ensure our remaining pristine streams are not degraded by discharge. As pointed out in testimony during the TCEQ meeting, there are viable alternatives to putting treated wastewater in the public waterways. These methods, including land application for beneficial use, have been successfully utilized in many small towns, at Hill Country summer camps, and around the Highland Lakes. Thanks to my father and others, Camp Wood found a beneficial use more than 40 years ago.

I have spent the past 22 years deeply engaged in resource protection for the Nueces River Authority within the same basin where I was raised and where I raised my children. My retirement will be effective April 30th, and my daughter, Julie Lewey, is stepping into my shoes at the river authority. And so, the family legacy continues, because loving rivers and working to keep them clean is buried deep in our DNA.

Will the fight for clean rivers ever be over? I’m betting on this new generation of water leaders and water warriors to get it done, once and for all. But they can use all the help they can get, so make sure you act on behalf of the river when the time is right.

Sky Jones Lewey recently retired after more than two decades as Resource Protection and Education Director at the Nueces River Authority.