Op-Ed: There Oughta Be a Law (But there’s probably not!)

Francine Romero | Texas Hill Country Conservation Network contributor

After visiting Gruene recently and encountering the explosion of new housing developments along the old rural roads leading to downtown, I was further disheartened to read that 252 duplex units on 22 acres are “coming soon.” I was left wondering how much more pressure can Gruene, New Braunfels, and all the Texas Hill Country withstand before significant cracks begin to emerge—compromising their value forever.

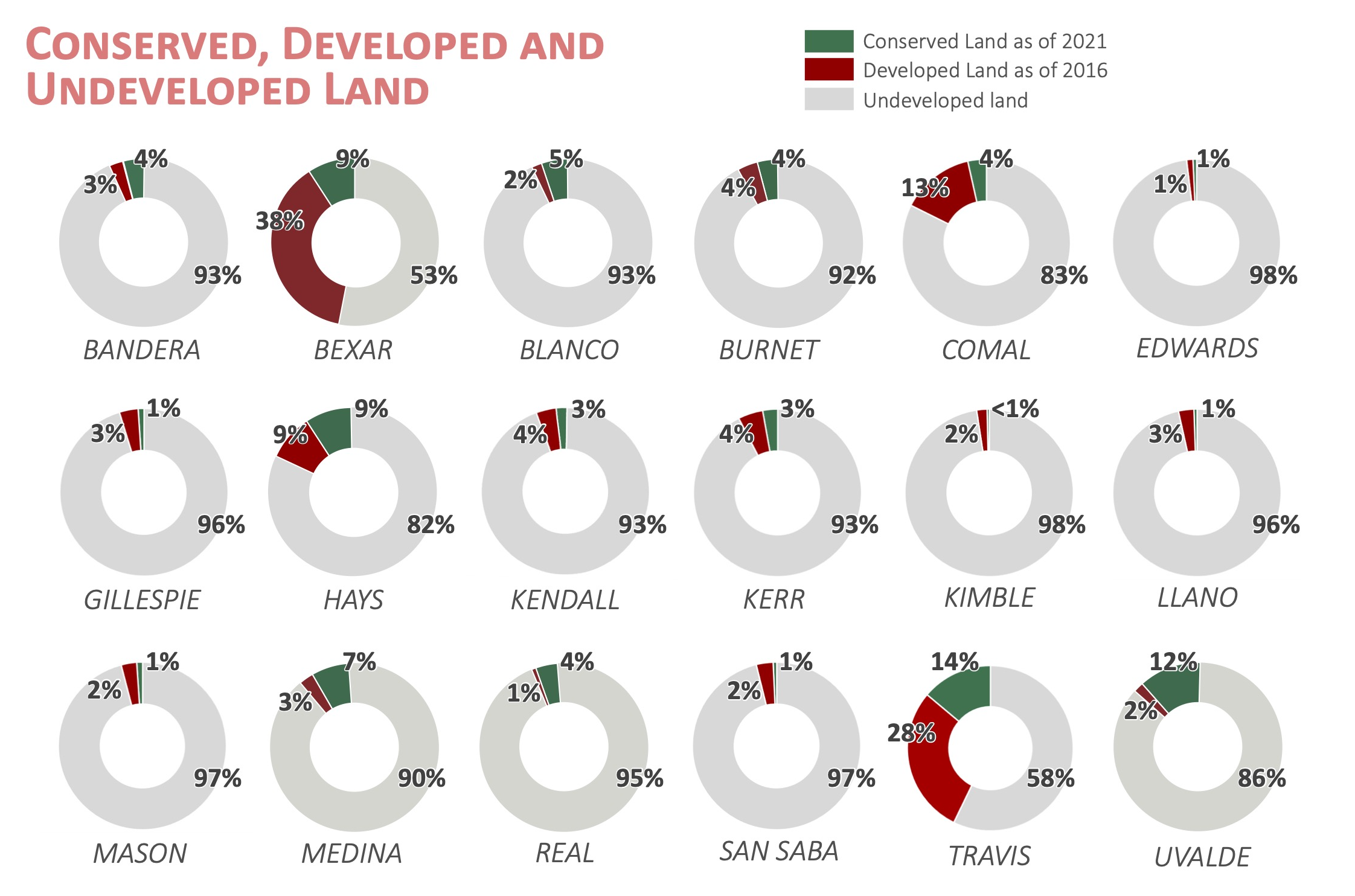

While few of us could reside in this region absent the growth of recent decades, the latest escalation of construction is alarming. The recent State of the Hill Country Report from the Texas Hill Country Conservation Network presents an unsettling truth—land development is necessary as population increases, yet its unchecked expansion may prove disastrous for environmental, aesthetic, and cultural/historical foundations.

Growth can visibly impact health, safety and welfare—such as streams compromised by wastewater discharge, loss of tree canopy, traffic gridlock, clouds of dust from extractive industries, and so on. We hear residents expressing disbelief at the absence of laws to slow this down. Yet, that is essentially our reality—state development regulations are minimal and often inadequately enforced, while local governments are constrained in their own responses.

In short, the legal environment and government systems are designed to facilitate land development. While attempts to curb its onward march are not futile by any means, communities committed to growth management must be both creative and resolute. Advocates need to determine if/when/how to utilize available tools and strategies.

The Texas Growth Machine

While immediate adoption of permanent growth moratoria may be the most tempting reaction, those are legally untenable devices. The only way to preserve land in perpetuity is through the instruments described in the Conserved Lands portion of the Report, particularly conservation easements—they cannot be dictated through regulation.

The closest any government entity can come to halting development is through a temporary moratorium, as Dripping Springs has recently enacted, and these are legally defensible only to provide municipalities a brief respite to plan accommodation for future growth. Similarly, calls to cease infrastructure provision are ineffectual.

Certificates of Convenience and Necessity (CCNs) granted by the state Public Utilities Commission not only empower, but obligate utilities to provide water and wastewater services within designated geographic areas. Even when such services are not feasibly provided by these purveyors, such as outside of CCN borders, projects can proceed by utilizing wells and septic systems, which may represent an even greater threat to surface and groundwater integrity.

Planning to the Rescue

More appropriate tools to attenuate development can be established through a new or revised municipal master plan. While many cities are already engaged in significant planning updates, it is imperative for citizens to advocate for elected officials to prioritize this process. Revisions are particularly timely now since most Hill Country municipalities’ plans are too dated to have anticipated recent growth. Importantly, this compels a community dialogue on how to use and/or protect land and other resources into the future.

One of the essential instruments in a typical master plan is the future land use map, designating the location of broad categories such as agriculture/ranching, residential, commercial, industrial, or mixed use, each of which in turn allows certain zoning categories. Open space may be designated but cannot be applied to privately owned land unless the owner has committed to some formal preservation mechanism.

These zoning categories are particularly pertinent to controlling density of prospective residential projects, and robust conversation on this end goal is critical, allowing citizens to consider implications of various choices. For example, a typical impetus is to reduce imminent density, say through minimum half-acre home sites and apartments limited to 15-20 units per acre. While that directive could provide immediate relief from the escalation, it may exert unanticipated consequences. If housing demand in this region withstands, then low-density rules will not restrict development so much as spread it out, generating greater ecological fragmentation and human impact.

Plans may also shape the aesthetics of growth, for example through lists of acceptable building materials, size, and styles, whether city-wide or in a historic area. And, perhaps most significantly, environmental impacts may be mitigated through binding requirements for resource protection (e.g., tree canopy preservation or restrictions on hillside constructions). Communities may consider incorporating principles of broader ecosystem support into development rules, such as the One Water integrated approach to water/wastewater infrastructure.

Beyond these specific tools, planning offers broader benefits. For one, regulations encompassed within a master plan possess greater legal gravitas than stand-alone ordinances, which can be more easily challenged as arbitrary or unfairly applied. Furthermore, updated plans allow communities to get ahead of development, effectively shaping the legal context well in advance of the next big project. When that familiar “coming soon” sign appears, it is likely too late to impose new restrictions.

Outside City Limits

Regrettably, binding comprehensive plans are pertinent only within the borders of a municipality or, to a certain extent, within its extra territorial jurisdiction (ETJ; the area beyond city limits where state law allows it to exert some regulations, but not zoning). But as the Report makes clear, significant growth is now occurring in unincorporated areas. Since counties possess minimal regulatory authority in Texas, development controls are virtually non-existent.

There are two paths around this barrier, both difficult to achieve. One is for the State to expand regulatory authority to counties. This is not unprecedented, but so far has only occurred on a limited basis to protect discrete and unique resources (e.g., Val Verde County in the area around Amistad Recreation Area). That could change if state leadership becomes convinced that the Hill Country represents such a significant resource and that it outweighs existing property rights protections.

The other path would be to return unilateral annexation authority to municipalities. This tool allowed cities to annex land prior to development (or at least full development), thereby shaping growth through its own ordinances. While some may have considered annexation a tool for the rampant spread of cities, it ensured responsible and consistent development practices. As the state legislature just revoked this authority in 2019, it is unlikely it will return any time soon.

To return to the power of planning, however, unincorporated communities may also engage in influential (albeit non-binding) planning exercises. If a developer is presented with a well-thought-out plan that outlines what residents view as a responsible project, a fruitful dialogue could ensue. Lacking a municipal planning team to guide this effort, communities may consult advocacy groups such as the Texas Hill Country Conservation Network to help kick-start and publicize the process.

Unify, Advocate, Monitor

I began this essay with the uncomfortable truth of development’s inevitability. In closing I return to the observation that many of us who share concerns have contributed to and benefit from this boom, a reality that may lead to unconstructive blaming and shaming narratives. On one side, the multitude of recent arrivals (moving here in 1997, I still consider myself a newbie) could be accused of trying to “close the gate” only after getting in themselves.

Conversely, these relative newcomers may condemn ranchers and others who sell off large tracts to developers, without fully understanding the overwhelming pressures they face. I noted that communities need to be creative and resolute in this effort; they also must be unified. Given the challenging legal context, it is time for residents old and new to cultivate an inclusive exchange of ideas to build consensus, in conjunction with a citizen network committed to advocating and monitoring for local and State level reforms. The call to action begins with these dialogues.

Francine Romero, PhD, is Department Chair and Associate Professor in the Department of Public Administration at The University of Texas at San Antonio. One of her research areas is local land use policy, including open space protection strategies. Dr. Romero was recently appointed to serve on the Board of Trustees for CPS Energy, is Chair of San Antonio’s Conservation Advisory Board, and past board member of the Hill Country Alliance.