New Reporting Requirements Ahead For State Funds Held Outside The State Treasury

Recently approved legislation, however, promises to shed additional light on this rather murky corner of the state’s finances.

![]()

The Texas Comptroller’s office is responsible for tracking and reporting on every dollar flowing to and through state agencies. Yet some state funds lie largely beyond public scrutiny — those held by state agencies and public colleges and universities in accounts outside the state Treasury, called locally held or “local” funds.

While state entities must report year-end balances for local funds to the Comptroller’s office for inclusion in the state’s Comprehensive Annual Financial Report (CAFR), there’s no detailed reporting on how they’re used.

Recently approved legislation, however, promises to shed additional light on this rather murky corner of the state’s finances.

Article IX, Sec. 17.09 of the 2017 General Appropriations Act (GAA) requires the Comptroller’s office and the Legislative Budget Board (LBB) to issue a biennial report on funds held outside the Treasury. With the new reporting process in place, elected officials and the public will be able to know just how much of this money the state has, and key details about its use.

State vs. local

State law allows many state agencies and all public institutions of higher education to hold local funds. These entities can hold and spend these funds without legislative appropriation, outside the normal budget process.

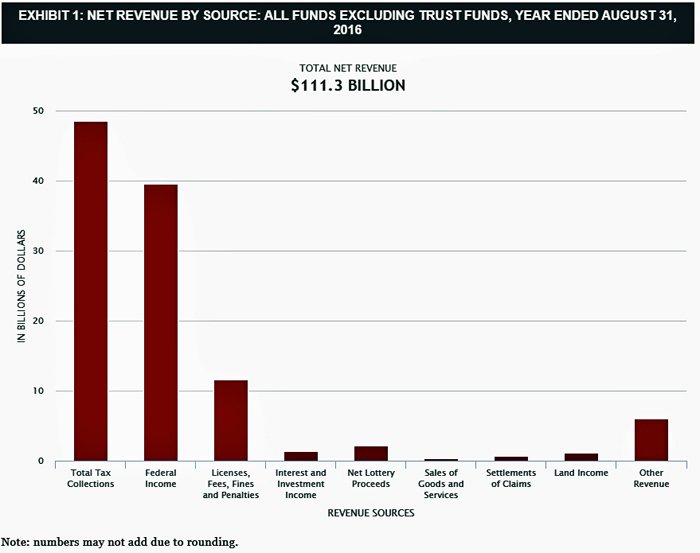

Most state funds are held within the Texas State Treasury. Revenue held in the Treasury comes from nine main sources (Exhibit 1). These funds are apportioned to agencies and institutions through the normal appropriations process every two years and are used to pay for a myriad of services such as health care, law enforcement and public education.

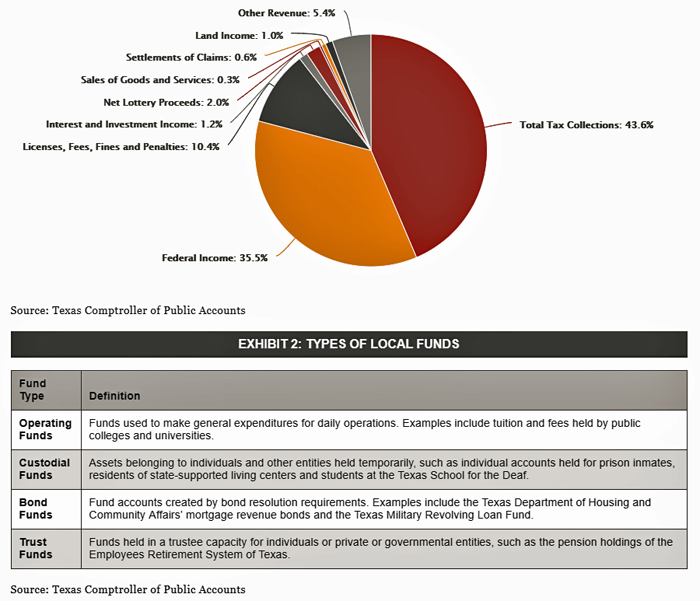

Local funds are held with the Comptroller’s office; its investment arm, the Texas Treasury Safekeeping Trust Company (TTSTC); and various private institutions. There are four basic types of local funds: operating, custodial, bond and trust funds (Exhibit 2).

![]()

Agencies can have more than one type of local fund, and local funds can be held by more than one entity. As a result, reporting on local funds is complex and piecemeal at best. The passage of the 2017 GAA should lead to a comprehensive accounting of them.

Billions outside the Treasury

Again, state agencies and entities with local funds self-report their end-of-year cash balances to the Comptroller’s office for inclusion in the CAFR, but they’re not required to report deposits and expenditures. If a local fund has a zero balance at the end of the fiscal year, the agency doesn’t have to report on it at all, even if substantial amounts flowed in and out of the fund during the year.

At the end of fiscal 2015, Texas’ agencies and public institutions of higher education held at least $7.5 billion in reported local fund balances. Of this amount, public colleges and universities accounted for $3.9 billion, the majority of it representing operating funds derived from tuition and fees. The University of Texas and Texas A&M University systems alone had a combined $2 billion in operating funds. State agencies held about $3.6 billion in local funds.

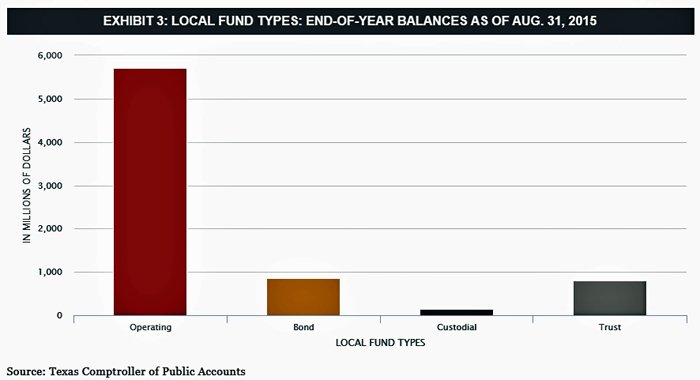

In some contexts, it makes sense to hold funds outside the normal budget and appropriations process. Custodial, bond and trust funds are collected and spent for specific, limited purposes such as pensions or public works projects. These categories, however, only account for about 24 percent of all local funds (Exhibit 3). Local operating funds, which support day-to-day operations and are spent similarly to legislative appropriations, make up the remainder.

Self-directed, semi-independent agencies

Some of the state agencies holding local funds are a type called self-directed, semi-independent (SDSI)agencies, a status granted by Texas’ SDSI Project Act of 2001. SDSIs are intended to be autonomous and self-sustaining, without state appropriations; they generate their own operating funds, which are held by TTSTC in interest-bearing accounts, and create their own budgets.

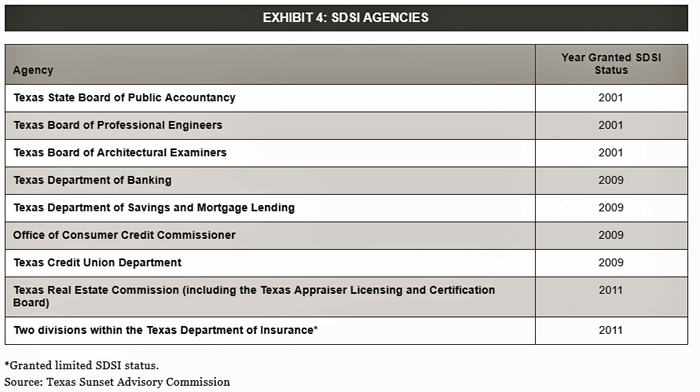

Three agencies, the Texas State Board of Public Accountancy, Texas Board of Professional Engineers and Texas Board of Architectural Examiners, were initially granted SDSI status by the 2001 act. Five more were subsequently granted SDSI status in 2009 and 2011 (Exhibit 4).

![]()

After some initial concern about minimal oversight, a 2013 Sunset Commission report showed the three agencies initially granted SDSI status were operating responsibly and that the SDSI Project Act was functioning as intended. The commission did, however, note several concerns about the potential for abuse and the need for additional oversight, and suggested additional requirements for SDSIs, proposing they:

- use the Comptroller’s uniform accounting system to make all payments (except for payments made to TTSTC);

- remit all administrative penalties to the State Treasury; and

- issue annual reports providing five years of financial performance data.

The Legislature adopted these recommendations for the three agencies created by the SDSI Project Act, but did not apply them to the other SDSIs. A subsequent Sunset report in 2015 noted “agencies [are] being granted SDSI status in a haphazard way, with inconsistent ongoing oversight,” and recommended the Legislature stop granting agencies this status until a consistent and comprehensive approach for managing the process could be created. The Legislature did not adopt this recommendation, however.

Effects on state finances

Holding funds outside the State Treasury diminishes the state’s General Revenue Fund interest revenue and thus reduces the amounts available for certification of the state’s budget. At least some of the billions in operating funds that account for three-quarters of all local funds could instead be earning interest income as do other, similar funds in the Treasury.

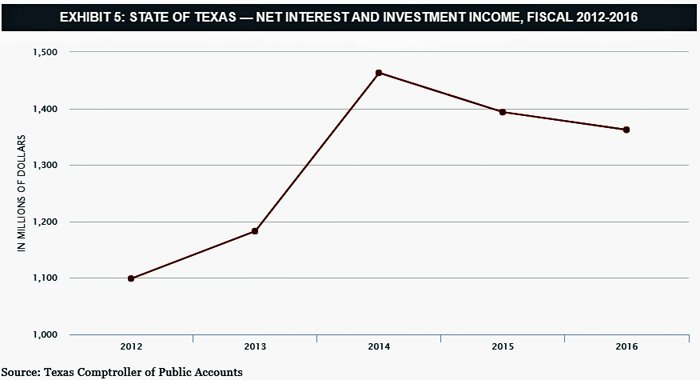

The State of Texas Annual Cash Report for fiscal 2016 reports the state netted nearly $1.4 billion in interest and investment income in that year (Exhibit 5). Data regarding interest earned by state funds held in private institutions aren’t available, but it seems safe to say that the billions in local operating funds generate millions of dollars in interest that never becomes general revenue.

Beyond the issue of lost interest, however, is the simple fact that the lack of information on local funds prevents the Legislature from basing its appropriation decisions on a full picture of the state’s finances. Some data on local funds, such as those of the original three SDSI agencies, is submitted to the Comptroller’s office, but little is known about funds held in private institutions.

Other states also allow for locally held funds, but know more about them. California, for example, requires all agencies with funds outside of its treasury to submit annual reports containing bank statements, balances, fund purposes and tax information. Illinois also publishes annual reports on locally held funds.

With its new reporting requirements, Texas too can begin to get a fuller picture of the activity and balances in these local accounts.

![]()

New reporting requirements

Under the new requirements of the 2017 GAA, any state agency that receives, spends or administers revenue held outside the Treasury will be required to submit financial data on the funds to the Comptroller’s office and LBB, which will prepare a report based on the data for each regular session of the Legislature. The new reporting requirements become effective on Sept. 1, 2017, with the first report due to the Legislature by the end of February 2019.

The report must include:

- the statutory basis for revenue held outside the Treasury;

- its allowable uses;

- a list of programs for which the revenue is or can be spent;

- estimated or actual revenues and expended or budgeted amounts by fiscal year for the most recently completed and current fiscal biennia; and

- the estimated or actual balance as of Aug. 31 of each fiscal year in the most recently completed and current fiscal biennia.

The lack of hard information about locally held funds makes it inherently difficult to determine whether they are being managed effectively, and obscures the picture of state revenues given by current reporting mechanisms. Without such data, legislators can’t make fully informed budget decisions. The new reporting requirements should go a long way toward filling this gap in our financial picture and provide information necessary for proper oversight. FN