Nursing in Texas: Charting the state’s nursing profession

By Jessica Donald and Lisa Minton

Nursing today has come a long way since the days of Florence Nightingale and Clara Barton and involves a broad scope of duties requiring extensive education and a technical skillset.

Nursing is one of the most in-demand fields in the health care industry. It also is one of the most challenging.

Nurses are responsible for providing high-quality and high-volume patient care while applying the latest medical technologies — often in stressful and difficult situations — and the need for nurses often outpaces the supply.

Nursing Workforce in Texas

In 2021, nearly 400,000 nurses were working in Texas, representing different levels of the profession: certified nursing assistants (CNAs), who are unlicensed but ancillary to the nursing profession; licensed vocational nurses (LVNs); registered nurses (RNs); and advanced practice registered nurses (APRNs) such as nurse midwives, nurse practitioners, and nurse anesthetists. Each category requires a progressively higher level of education and training.

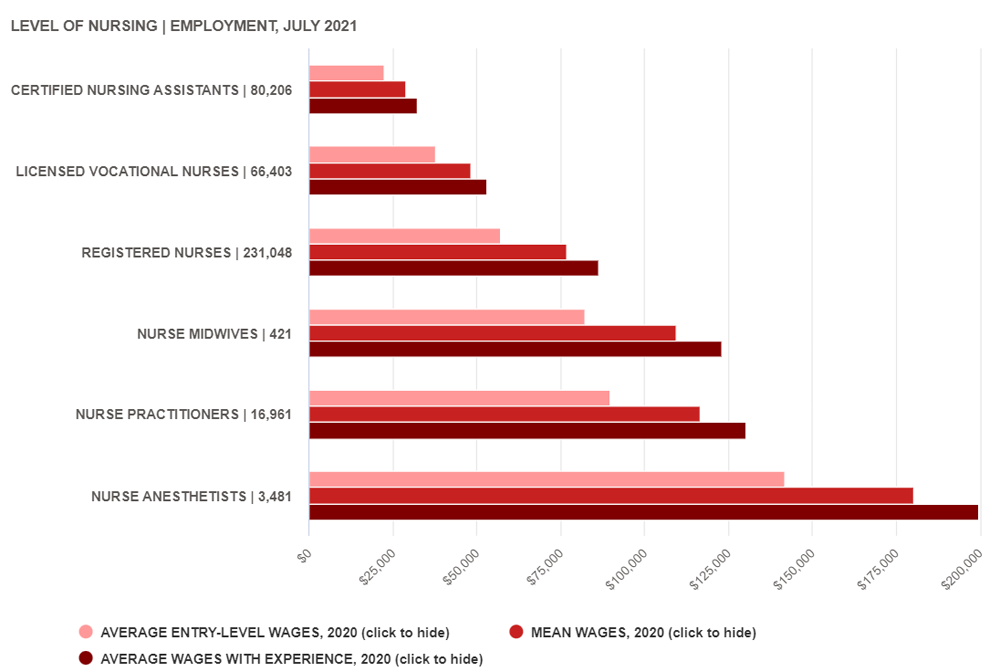

Fifty-eight percent of nurses in Texas are RNs, followed by LVNs at 16.7 percent and CNAs at 20.1 percent. APRNs are a comparatively small group, comprising just 5.2 percent of Texas nursing employment, but they command much higher wages (Exhibit 1).

The annual wages of RNs in Texas typically start at $57,300 and increase to $86,500, depending on their level of experience. On average, nurse anesthetists are paid the most, with some earning more than $200,000 per year.

.

EXHIBIT 1: TEXAS NURSING WORKFORCE PROFILE

.

According to the Texas Board of Nursing’s 2021 Annual Report (PDF), new licenses are growing the fastest for advanced practice registered nurses in Texas — a 12 percent increase from fiscal 2020 to fiscal 2021. New RNs increased by 3.5 percent during the same time, but the number of vocational nurses declined by 1.7 percent.

Though 41.1 percent of Texas nurses work in hospitals, nurses also fill a variety of positions in other health care settings such as long-term care facilities, doctors’ offices, schools, and businesses (Exhibit 2).

.

EXHIBIT 2: TEXAS NURSING WORKFORCE BY INDUSTRY, JULY 2021

.

| Industry | Nursing Assistants | Vocational Nurses | Registered Nurses | Nurse Midwives | Nurse Practitioners | Nurse Anesthetists | Total Nurses | Share of Nurses |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General medical, surgical and specialty hospitals | 23,637 | 7,912 | 127,113 | 118 | 3,811 | 1,154 | 163,745 | 41.1% |

| Nursing, long-term care and assisted living facilities | 32,924 | 17,879 | 10,420 | 61,223 | 15.4% | |||

| Home health care services | 11,290 | 17,894 | 31,017 | 964 | 61,165 | 15.3% | ||

| Offices of physicians and other health practitioners | 1,321 | 8,954 | 16,199 | 251 | 9,076 | 2,079 | 37,880 | 9.5% |

| Outpatient care centers | 779 | 2,825 | 11,098 | 41 | 1,273 | 108 | 16,124 | 4.0% |

| Employment services | 2,849 | 2,203 | 4,895 | 200 | 10,147 | 2.5% | ||

| Elementary and secondary schools | 540 | 1,278 | 5,740 | 7,558 | 1.9% | |||

| Individual and family services | 1,729 | 648 | 1,471 | 96 | 3,944 | 1.0% | ||

| Psychological and substance abuse hospitals | 741 | 2,982 | 109 | 3,832 | 1.0% | |||

| Colleges, universities and professional schools | 531 | 2,645 | 8 | 505 | 98 | 3,787 | 1.0% | |

| Residential intelligence and developmental disabilities, mental health and substance abuse facilities | 861 | 906 | 1,767 | 0.4% | ||||

| Other | 4,276 | 4,632 | 17,468 | 3 | 927 | 42 | 27,348 | 6.9% |

Source: JobsEQ

Nursing Shortage

The quality of health care and Texans’ access to it could be at risk due to a nationwide nursing shortage. As our population ages and the demand for health care continues to grow, the number of nursing school graduates simply is not keeping pace with demand.

In a 2019 survey by jobs site CareerCast, RNs were the fifth most in-demand profession in the United States.

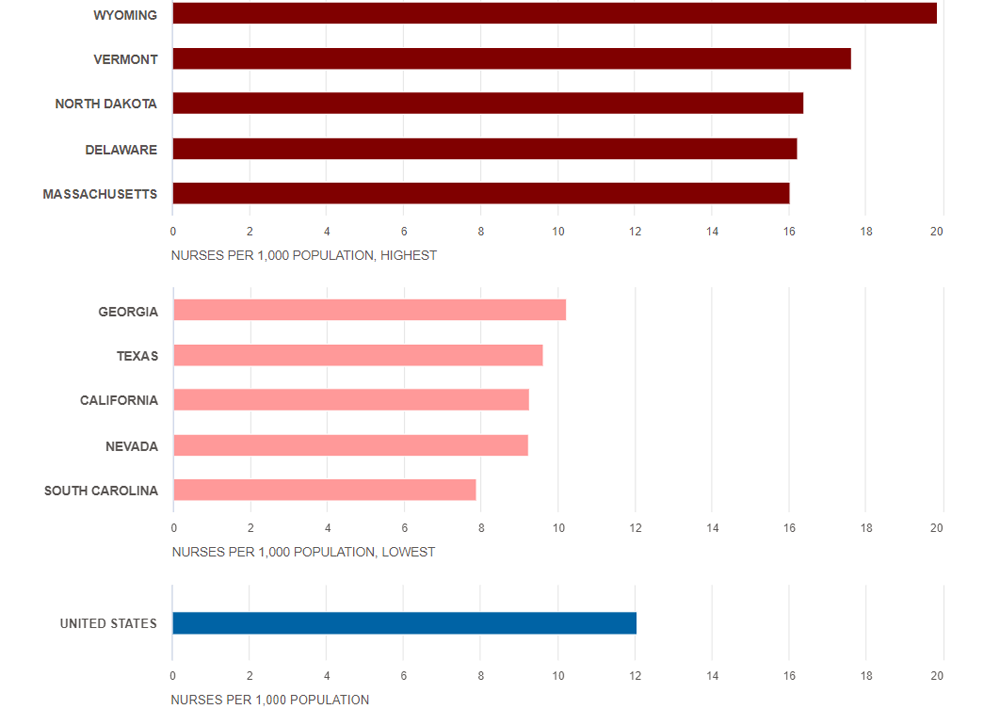

According to a March 2022 NurseJournal analysis of U.S. Bureau of Health Workforce data, Texas had the fourth-lowest nurse-to-population ratio among all states, with only 9.25 nurses per 1,000 residents (Exhibit 3).

.

EXHIBIT 3: NURSES PER 1,000 POPULATION, 5 HIGHEST AND 5 LOWEST STATES

.

The Texas Center for Nursing Workforce Studies (TCNWS), part of the Center for Health Statistics at the Texas Department of State Health Services, conducted a March 2021 study of the projected demand for nurses in Texas (PDF).

The Updated Nurse Supply and Demand Projection, which used 2018 as its baseline year and projected nursing demand through 2032, concluded that Texas faces an increased shortage in every nursing category if, as expected, demand continues to outpace the supply.

The supply of vocational nurses, for example, is expected to grow 13.8 percent by 2032, but the demand will grow by 45.5 percent. The outlook for RNs also is dire: The study estimates that 16.3 percent of the projected demand for registered nurses in 2032 will not be met.

Although the demand for nurses is expected to increase in all settings, the largest shortage of RNs is expected primarily in inpatient hospital settings.

Shortages of vocational nurses are expected to fall on inpatient hospital settings and nursing homes almost equally (see “Elder Care in Texas”). Shortages are expected to be worse in rural areas of the state.

The state’s aging population — which comes with a higher degree of chronic medical conditions such as diabetes, obesity, and dementia — puts pressure on Texas’ already overburdened nursing workforce, and the COVID-19 pandemic hasn’t helped.

Because of the pandemic, nurses have been working longer hours, seeing more difficult cases, and dealing with the constant threat of exposure to a deadly disease — with a dramatic impact on the nursing workforce.

“COVID-19 has really increased the shortage,” says Texas Board of Nursing’s executive director, Kathy Thomas. “Nurses are walking out. They’re worn out, they’re burned out and they’re stepping away from their jobs.”

Thomas is particularly concerned about what she called a “severe” shortage of vocational nurses in long-term care facilities such as nursing homes. “Many new nursing graduates want to go work in the emergency room or the ICU, not a nursing facility — but that’s where the need really exists.”

.

ELDERCARE IN TEXAS

.

More Texans are turning 65, but the number of nursing facility employees needed to care for them isn’t keeping pace.

Almost 13 percent of Texans — 3.7 million people —are in the 65 and older age bracket, and the figure is expected to rise to 17 percent by 2050, according to the Texas Health and Human Services Commission. As many as 70 percent of people hitting 65 can expect to need long-term care at some point, according to Long-TermCare.gov.

AGE of Central Texas

Since COVID-19 was declared a pandemic, the nursing home industry has lost almost 400,000 jobs nationally, with many employees leaving for jobs with better pay and working conditions.

The Texas Health Care Association (THCA) and the education and advocacy group LeadingAge recently surveyed more than 200 nursing facilities and more than 30 assisted living facilities, and the results illustrate a dire situation in the state as well.

All surveyed facilities had open positions for Certified Nurse Aides, and 94 percent had unfilled Licensed Vocational Nurses spots. At 63 percent of those facilities, no one had applied for the open positions.

Such a severe shortage of staff and applicants moves more of the caregiving to families who might not be prepared for those duties.

Though Texas saves money in care costs (PDF) when families provide for their aging loved ones, many caregivers who choose not to work or are unable to work outside the home while providing care forfeit potential income and limit their discretionary spending. The latter helps generate more sales tax revenue — currently 59 percent of Texas’ state collections.

“What I see in general is [that] family caregiving is largely a fly-by-the-seat-of-your-pants thing,” says Annette Juba, chief program officer with AGE of Central Texas, an organization focused on providing information and resources for older Texas adults and their caregivers. “In our society, there is so much focus on raising children, and there isn’t a whole lot of cultural knowledge around [elder] caregiving.”

University of Texas

Last year’s third called special legislative session provided some relief for Texas’ skilled nursing industry. Lawmakers agreed to allocate $378 million in grants from the federal American Rescue Plan Act to nursing homes and assisted living facilities.

Some of the money is being used for recruitment and retention bonuses for care positions, according to the THCA. These positions and others focused on eldercare outside of facilities, will continue to be in high demand.

“Given rapid population aging in Texas, more institutional arrangements are needed that address the preferences and needs of older adults and their caregivers,” says Jacqueline Angel, professor of public affairs and sociology at the University of Texas at Austin Center for Health and Social Policy at the LBJ School. “State agencies serving the elderly and family caregivers are using new technologies to creatively disseminate as much information about senior services as possible to as many as possible. These agencies hope to enable frail elderly people to find the help they need to stay in the community and remain independent in their own homes.”

Education and Licensure

Education has been one of the key advancements in the nursing profession. In the late 19th century, most student nurses received on-the-job training in a hospital setting. As medical care became more complex, the hospital-based education model was supplanted by training programs at colleges and universities.

Today, more than 120 Texas colleges, universities, and private schools offer nursing degrees and certificates of various levels.

Texas nursing schools offer five different undergraduate and graduate degree programs requiring from one to six years of study. (The certificate or diploma for nursing assistants is not included in this list because, although nursing-adjacent, this designation technically is not considered nursing education.)

- Certificate or diploma (12-18 months) for LVN.

- Associate in Nursing (two years) for RN.

- Bachelor of Science in Nursing (four years) for RN.

- Master of Science in Nursing (two years, not counting prerequisite undergraduate degree) for both APRN (such as nurse midwife, nurse practitioner, or nurse anesthetist) and non-APRN such as nurse administrator.

- Ph.D. for nursing researchers or Doctor of Nursing for APRN and non-APRN majors (four to six years, not counting prerequisite degrees).

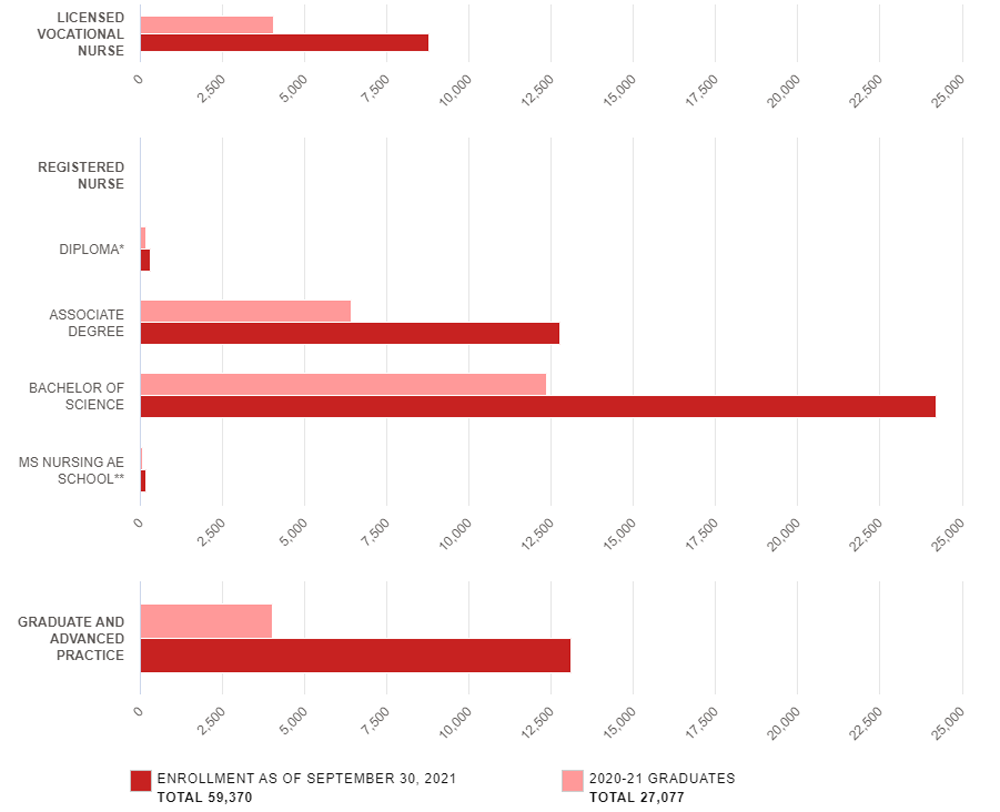

According to TCNWS reports, Texas nursing programs produced more than 27,000 graduates in the 2020-21 academic year (Exhibit 4).

.

EXHIBIT 4: TEXAS NURSING ENROLLMENT AND GRADUATES, 2020-21 ACADEMIC YEAR

.

**AE = Alternative Entry and is available for students who already hold non-nursing bachelor’s degrees.

Source: Texas Center for Nursing Workforce Studies

In 2021, the state had 85 vocational nursing programs, offered primarily through community, state, and technical colleges.

Data from TCNWS indicate that 49 vocational programs were unable to admit all qualified applicants for reasons that included lack of clinical space, limited classroom space, and lack of faculty.

TCNWS also reported 126 registered nursing programs in Texas during 2021 offered by community colleges, universities, and private schools.

Most of them (81.7 percent) offered alternate education tracks in addition to basic programs. In the state, 86 registered nursing programs were unable to accept all qualified applicants for reasons that included lack of clinical space and lack of faculty.

The Texas Board of Nursing is responsible for regulating not only the practice of nursing but also the state’s nursing education. The board’s director of nursing, Kristin Benton, says there is a need for additional nursing school faculty.

“We don’t have enough qualified faculty,” says Benton. “If we don’t address the faculty shortage, we can’t increase the number of nursing graduates because we can’t take any more students in those settings.”

She cited comparatively low faculty pay as a deterrent for many prospective professors, who potentially can earn twice as much working in a clinical setting.

Increasing Access to Nursing

The need for well-educated and highly skilled nurses has led to many innovative programs within nursing education that allow more Texans to enter the field.

For example, Alamo College in San Antonio offers the Military to Registered Nursing Career Mobility Track, a three-semester program that allows those who trained as Army combat medics, Navy corpsmen, or Air Force medical technicians within the past 10 years to more easily earn an associate degree in nursing.

Some nursing programs are being made available to Texas high school students as well. As of 2020, Texas had seven vocational nursing programs, offered in partnership with local community, state, or technical colleges and usually taught by nursing program faculty.

Hudson High School in Lufkin, for example, offers its seniors the option of enrolling in a vocational nursing program that continues into postsecondary courses.

Online Options

Online courses often are less costly than campus classes, and innovative web-based technologies allow students to participate in classes in real time. Most online nursing programs in Texas don’t impose class credit minimums, so students can take as few or as many classes as they are able, proceeding at their own pace.

Texas State University’s St. David’s School of Nursing offers a Master of Science in Nursing program online. The program was named one of the best online nursing master’s programs by U.S. News and World Report for 2022.

The program consists of online classes, recorded lectures, face-to-face instruction, and skills practice two weekends each semester.

In 2017, the 85th Texas Legislature authorized the Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board (THECB) to allow certain public community colleges to offer bachelor’s degrees in nursing — provided they meet all Texas Board of Nursing requirements.

By the end of fiscal 2021, 13 public community colleges had been approved to offer these nursing programs.

Nursing Shortage Reduction Program

The Nursing Shortage Reduction Program (NSRP) was enacted by the 77th Texas Legislature in 2001 to increase the number of registered nurses in the state.

The NSRP allows THECB to administer dedicated funds to Texas nursing education programs. In 2009, those programs gained the ability to use NSRP funds at the time of student enrollment rather than at graduation.

The NSRP program has been funded since 2004, with the 87th Legislature allocating $18.8 million for the 2022-23 biennium. A prorated portion of the funds must be paid back, however, if certain targeted goals are not met.

Though the number of Texas nursing graduates has increased since the establishment of NSRP, a recent legislatively mandated evaluation of the program criticized the complexity of NSRP spending formulas and the uncertainty of funding, which makes it difficult for institutions to budget and hire permanent nursing faculty.

What’s Next for Nurses?

Nurses have always played an essential role in patient care, but today, that role is even more important.

The nursing profession continues to undergo changes as it adapts to the needs of modern health care, and Texas nurses have continued to maintain a high standard of education and professionalism.

The need for nurses at all levels is growing in Texas, however. The state’s nursing community is trying to step up to meet the challenge, but as Thomas summed it up, “We have a long way to go.” FN

Source: Office of the Texas Comptroller