Texas Has More Kids Eligible For Free Summer Meals. Why Is The State Feeding Fewer?

![]() After peaking in 2013, the number of students who received free summer meals at Texas schools dropped last summer. No one seems to know exactly why, but one possible reason is lack of transportation.

After peaking in 2013, the number of students who received free summer meals at Texas schools dropped last summer. No one seems to know exactly why, but one possible reason is lack of transportation.

By, Aliyya Swaby

Editor’s note: This is the first of a two-part series about the declining participation in Texas’ summer meals programs for students.

When Evelyn Delgado saw a banner outside her daughter’s Houston school advertising free breakfasts and lunches this June, she figured it was an opportunity to give her 7-year-old good food and a chance to get out of the house.

Delgado used to work at a local Fiesta Mart and leave her two kids with a babysitter, before she realized that paying the sitter was eating up her paltry wages. Now a stay-at-home mom with a husband who works in maintenance, she said the summer program helps feed her kids, who are eligible for free meals during the school year.

“We went [to the school for meals] the whole time,” she said. “As long as they don’t close it down, I think it’s doing great.”

But Delgado’s daughter is among a shrinking number of students who participate in federally funded summer meals programs across the state. Texas missed out on about $56 million in federal money in 2016 — more than any other state — because it could not draw enough hungry kids to its summer meals programs, which are available to kids who qualify for free or subsidized meals.

In 2011, the state passed a law requiring school districts to offer free meals to students for at least 30 days during the summer break, if at least 50 percent of their students are eligible for free and reduced school lunches. The free meals are available to any student, regardless of whether they’re enrolled in the district.

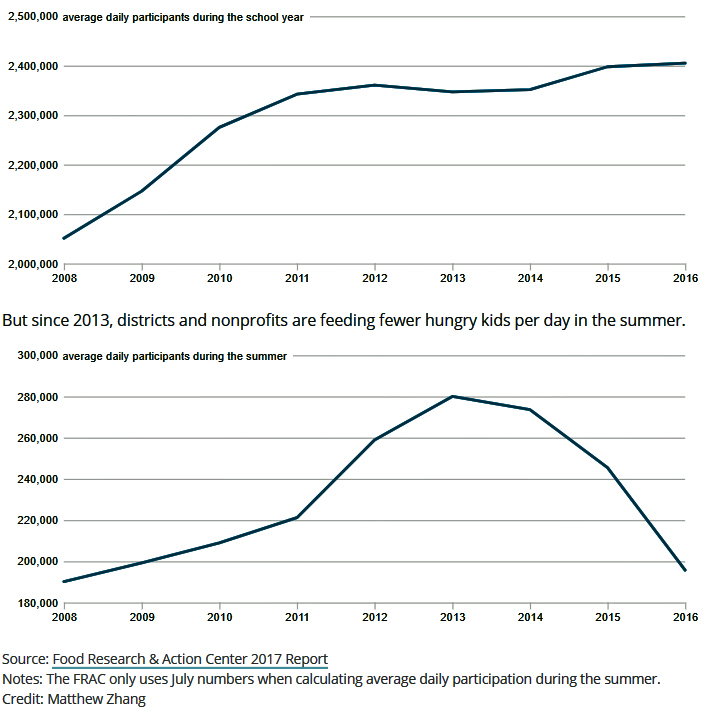

After peaking in 2013 at around 280,000 students per day, last summer Texas’ participation rate took a big plunge: The average number of Texas kids served meals each day in July 2016 was 20 percent lower than the previous July, and the state dropped from 39th to 48th in a national ranking of such summer programs, according to a recent report from the nonprofit Food Research and Action Center.

Yet the average daily number of Texas kids who can’t afford meals during the school year increased slightly to 2.4 million between 2015 and 2016.

“It is disappointing, to be honest, given the extensive statewide efforts to promote participation,” said Erin Nolen, assistant director of research at the Texas Hunger Initiative, a nonprofit that partners with the state to support summer meals sponsors.

Why is participation dropping?

No one knows exactly why fewer kids are taking advantage of free summer meals, but there are many hypotheses. One reason cited by school districts is state and local budget cuts, which have caused some districts to scale back summer programs like sports or tutoring that attract students to their campuses.

Kids who come to school for those programs are more likely to take advantage of summer meals. That helps combat a problem that accompanies hunger during the summer, especially for low-income kids: the “summer slide.” Studies show low-income students are more likely to lose a few months of reading skills during the summer, falling behind their higher-income peers.

To save money because of a tight budget last year, El Paso ISD cut the number of summer meal sites at its schools. The large border school district served about 20,000 fewer lunches from June through August 2016 than the year before, according to state data. This year, the district cut back on its July summer enrichment programs at several campuses, which meant fewer students being bused to the schools.

“If you have programs and kids are busing in for programs, they’re there and they eat,” said Judy Estrada, assistant director of food services for El Paso ISD. “If there are no buses or transportation … kids can’t get into the programs and don’t eat.”

Texas’s summer meals participation has not kept up with an increase in need

According to a national report, the average number of students considered at risk of hunger per day has gradually increased, with more students eligible for free and reduced lunch during the school year.

![]()

Catherine Wright Steele, administrator at the Texas Department of Agriculture, which administers the summer meals programs, offered other possible reasons for the drop in participation. Transportation is always a challenge for school districts and nonprofits offering meals, she said, because the federal money — which flows through a pair of U.S. Department of Agriculture programs — does not cover that expense.

Many Texas school districts offer meals and bus transportation in June, when students are in summer school, but they often can’t afford to keep the buses running in July and August after summer school ends, officials said.

That could mean that hungry kids whose parents aren’t available to drive them to school can’t take advantage of free meals, Steele said.

The state agency conducts regular audits to ensure that school districts and nonprofits that receive federal reimbursement are following the rules for distributing and counting meals, Steele said, but it doesn’t have plans to do a statewide survey to investigate the recent dip in participation.

Meanwhile, the state has participated in several national pilot programs over the past five or six years to figure out how to increase participation, and next summer it will be part of a federal pilot program that will give low-income families additional money for food on either Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) or Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) transfer cards so families won’t have to travel to a specific nonprofit or school district for a free meal.

“There’s still work to be done in Texas,” said Signe Anderson, a policy analyst at the Food Research and Action Center and co-author of the report. “There are kids that are missing out on these meals who have access during the school year.”

More schools opt out of offering programs

Another reason that fewer kids are getting free meals during the summer might be that more schools have stopped offering them.

School districts that are required to offer summer meals under the state law can apply for waivers to opt out if they can show that high start-up costs and low participation would mean serving meals would cost them money, even with the federal reimbursement. They have to identify another school district or organization that could serve those kids instead.

This summer, 236 districts received a waiver, a slight increase from last year, Nolen said.

Jasmyn Spivey, 6, carries her lunch to the table at Jarvis Christian College in Hawkins, one of 77 sites the East Texas Food Bank sponsors to serve free food to hungry students. Laura Skelding for The Texas Tribune.The majority of school districts that applied for waivers are in rural areas, with most saying transportation was the main barrier. With students unable to get to schools that are often far from their homes, rural school districts often “don’t believe they will have a high enough participation rate to come close to offset the costs,” Nolen said.

Transportation can also be a problem in cities, where mazes of highways can prevent kids from walking to schools outside their neighborhoods.

That’s the case at Dallas ISD, which served about 13,000 fewer lunches in the summer of 2016 than 2015, according to state data.

For the kids can’t get to the meals, Dallas administrators are considering ways to bring the meals to them.

“We might have some sort of bus or a vehicle that’s air conditioned, and you make that your little mobile feeding site,” said Michael Rosenberger, executive director of food and child nutrition services for Dallas ISD. “It saves students from making a hazardous trip.”

Some districts have teamed up with community organizations to serve meals closer to where kids are, which could mean giving out sandwiches at a park, not the local school.

That means “tapping into community members who are really in tune with their local areas. They’ll know if kids are hanging out at the park or community pool,” Nolen said.

Finding better ways to get meals to students, or vice versa, is crucial, according to educators and experts who are concerned about the tumbling numbers in Texas. In areas with high rates of hunger, they said, kids who don’t find free meals through the program are likely scrambling to get unhealthy, cheap food, if they’re eating at all.

“They’re not eating any kind of balanced meal. They’re probably scrounging at home trying to find the last little beans or rice on the pantry shelf,” said Estrada, the El Paso ISD official.

With six kids under the age of 10, Kaylee Houser has made the eight-minute drive to Coronado High School in El Paso weekdays this summer to supplement their meals. A recent transplant to the city from New Jersey, Houser said she wouldn’t have known the local high school was serving free meals if a few other moms from her kids’ school hadn’t pointed it out.

“If you don’t have a high school student, you wouldn’t go to the school and know about it,” she said. “The publicizing needs to increase because a lot of times, we’re the only ones in the whole gym.”

Houston tries to reverse slide with advertising

Houston ISD has tried to reverse its slide — the district served about 50,000 fewer lunches in the summer of 2016 than the summer before, state data shows — by getting creative with its advertising. This summer, the district spent $20,000 to hang banners in schools across the district and put 5-by-10-foot decals on 24 district-owned delivery trucks driven around the city.

“We need something that is constant out there, where people get to see it often,” said Hernan Urrego, Houston ISD’s operations manager.

Houston ISD officials attributed part of their decreased participation to a fluke — after a testing company made a series of major flubs delivering scores for state standardized tests in 2016, the state said students who scored poorly didn’t have to attend summer school that year.

With about three-fourths of the district’s students getting free or discounted meals during the school year, kids who don’t show up in the summer are likely going hungry, said Keith Lewis, Houston ISD’s senior operations manager.

And even if they show up, he said, “the last meal they get here may be the meal they get that day.”

This story originally published by The Texas Tribune.