The Future Of Cape’s Dam: What Repair Or Removal Means For The River

![]() The issue has been hotly debated in San Marcos, and many who have spoken out in defense of the dam have relayed damage to their personal property and/or anonymous threats to their wellbeing…

The issue has been hotly debated in San Marcos, and many who have spoken out in defense of the dam have relayed damage to their personal property and/or anonymous threats to their wellbeing…

by, Candice Brusuelas, #SaveTheSMTXRiver

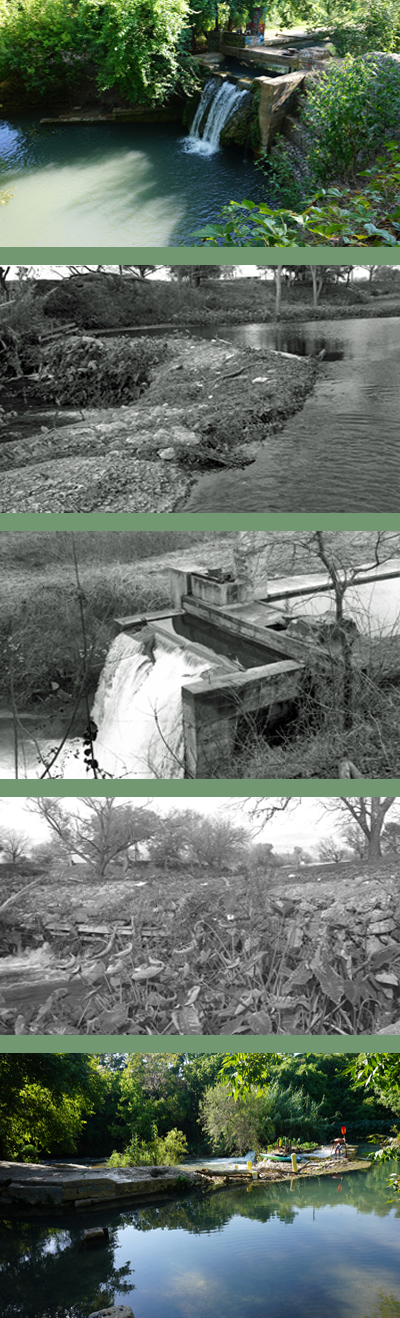

Cape’s Dam is damaged. There’s no question that it’s unsafe for recreation, unattractive, and preventing the utilization of what could be beautiful park space on the San Marcos River. What’s less clear is whether removing or reviving the dam will better benefit our community.

The issue has been hotly debated in San Marcos, and many who have spoken out in defense of the dam have relayed damage to their personal property and/or anonymous threats to their wellbeing. This isn’t to say that one “side” is definitively right or wrong, good or bad, but that emotional and personal involvement in the matter has hindered the conversation and left an ominous void in what should otherwise be a community discussion.

But let’s start with what we do know.

- Cape’s Dam is over 150 years old. It provides enough water to sustain the mill race channel. Both remove/repair advocates believe that without the dam, that mill race will have little to no water in it, leaving a bare trench with exposed tree roots and eventual deterioration.

- In 2000, a breach in Cape’s Dam led to the relocation of many wild rice plants, from the San Marcos River to the state fish hatchery. The damage lowered water levels, as recorded in the San Marcos Daily Record and Austin American Statesman. The dam was never fully repaired, but patched up for a later repair that never happened.

- San Marcos River is a federally protected environmental habitat for the Texas Wild Rice and Fountain Darter fish, which means that any alterations to this habitat need to be closely monitored and researched. With removal, part of that habitat, the millrace, will be lost.

- The mill race and Thompson’s Island have long been a place for beginner canoers and kayakers to learn, a place for youth groups to retreat, and a place for disabled and handicapped recreationalists to access the river.

There are many aspects to consider, including the historical value discussed in Part 1 of this article. Now that we know what it is and its past, here are some ways altering the dam could affect us here and now.

The Community

The San Marcos River has become a float-friendly zone for tourists and locals alike. We are a hotspot for tubers, where hundreds of tubes floating lazily down the river every weekend.

But kayaking and canoeing, in particular, has long been a San Marcos tradition that is disappearing with fewer access points for boaters. The damage to Cape’s Dam has narrowed access to the river, especially to beginners and disabled recreationalists.

Disabled veterans, particularly, accessed the river at the entrance to the millrace at Cape’s Road. Canoers and kayakers were able to easily put their craft into the gentle flow of the millrace channel and work their way upstream to the main channel at Cape’s Dam.

Other access points, like City Park, have steps down to the water. But the access point to the millrace has been closed since the city took ownership of the area in 2014, because of the unsafe conditions of the dam. Some still access this point, but in a dangerously small space up against the road.

Longtime San Marcos canoer Tom Goynes doesn’t like dams, but he does enjoy rapids.

“There’s a fine line between a dam and a rapid. They both hold back water except one of them is made of boulders and it’s fun to shoot through in a canoe or kayak,” he said.

Goynes believes rapids would serve the same purpose for Cape’s Dam as they have for Rio Vista. This way, the millrace would continue to be filled and the dam would no longer obstruct downstream canoeing.

Goynes once owned a kayak and canoe rental, now owned by Duane TeGrotenhuis and renamed TG Canoes.

Safety is also a concern for youth groups and beginner canoers and kayakers. TeGrotenhuis stopped renting out watercrafts after City Council voted to remove the dam. The main channel of the river is not safe for his customers, he says.

“The (main) channel has a lot of switchbacks. It twists and curves and winds a lot,” TeGrotenhuis said. “It’s dangerous to be honest. And if we take out the dam and people have to go down the right-hand side, we will inevitably lose somebody sooner or later.”

TeGrotenhuis also regularly rented to Boy Scouts and other youth groups who came during the summer for canoeing, and says he always had the groups use the left (millrace) channel.

The Environment

The stretch of river affected by Cape’s Dam is protected by Texas Parks and Wildlife and US Fish and Wildlife as a critical habitat for endangered species. Specifically, the river is home to Texas Wild Rice and the Fountain Darter.

The stretch of river affected by Cape’s Dam is protected by Texas Parks and Wildlife and US Fish and Wildlife as a critical habitat for endangered species. Specifically, the river is home to Texas Wild Rice and the Fountain Darter.

A local endangered species biologist, who does not want to be named because of the aforementioned retaliation, told us that this federal protection requires that any project that will impact the area must be reviewed closely.

“They not only have to evaluate the impact of each individual species, but they also have to evaluate the impact of the critical habitat as well,” she said.

With a federal permit to work with endangered species in Texas, she has been concerned with the issue of Cape’s Dam since the issue after the City Council voted for removal in 2016. She also said that removing the dam would completely disrupt that critical habitat, the information for which is backed by many studies on dams pre- and post-removal.

“(Removing the dam is) going to change the way the system has been for the last 150 years since the dam has been in place. It’s going to increase flow, it’s going to make the water shallower,” she said. “When you have those two things happen, you have a change in your (riverbed/habitat) composition.”

Not only will the environment be drastically altered, but without the dam, the millrace, a big area of that federally designated critical area, will no longer exist as a habitat.

As an environmentally protected area, we have a responsibility to do proper evaluations and consultations before making such a drastic change to the river. What some argue would return the river to its “natural state” by removing the dam is to alter the natural way the river has adapted to, and thrived with, the dam in place.

With that in mind, restoring would maintain conditions that have existed and allowed the species to thrive. For restoration, we wouldn’t need a slew of studies to evaluate its impact.

The dam has shaped today’s San Marcos River, as have many other dams. We saw an example of the Texas Wild Rice’s dependence on the dam in 2000 when the dam breached and water levels dropped too low to immerse the TWR, as chronicled by the San Marcos Record.

According to the article by now-editor Anita Miller, the water upstream from Cape’s to Rio Vista Dam lowered over a foot, necessitating the relocation of TWR to save it. USFW stated in the article that 25 percent of the TWR in the river at the time was in that specific stretch of water. TWR plants were left exposed and dying on the surface.

This earlier evidence is indisputable. TWR will struggle in lower water levels, which current removal advocates also argue will even out to normal levels with sediment displacement after the dam is removed. Even if it does, will it still be hospitable for the TWR? Or will the TWR die, exposed, before the sediment rearranges itself?

The current research on which the city and the San Marcos River Foundation bases their “remove” verdict is a single study by Thom Hardy. While his research is not thorough, it’s not our job to say whether his verdict is right or wrong. The problem is that this is only one study, and this study has neither been peer-reviewed nor publicly released.

Other existing research (our biologist says the San Marcos is the most-studied river in Texas) suggests it’s better for the habitat to repair the dam.

What’s currently happening?

The city has not explored remedy options thoroughly. According to Assistant Director of Comm Services, at San Marcos Parks and Recreation, Drew Wells, US Fish and Wildlife was the driving force for dam removal. Since, USFW has withdrawn their funding for removal, and Wells says the city is reassessing their options, but gave no further details.

The San Marcos Historical Commission discussed the issue on Sept. 6, voting to discuss designating the dam and mill as a historical landmark. The discussion will take place at the Oct. 4 meeting.

Goynes suggests a Rio Vista-like model of rapids, which also act as a fish ladder for environmentalists concerned about fish passage. The water would be maintained in the millrace and canoers can easily pass farther downstream.

Plans for repair have been made in the past, but lacked funding and support. A 1998 proposal for Capes Dam repair not only acknowledges the need for the structure, but a need to improve upon it. The proposal sought to create a dam similar to the wire-wrapped rock structure that exists, but one that provided a smooth surface to prevent the catching of debris in the open weave of wire. It also proposes control works to manage water levels in periods of drought, to maintain a healthy water level for wild rice.

According to the proposal, “The Corps of Engineers has used similar structures in New Mexico with good success. These structures have proved to be economically feasible and able to withstand flood events with little to no repairs.”

This structure was estimated at approximately $608,000 in total, and also supported by the Austin Ecological Services. But, alas, the project was not funded and shuffled aside. The dam was patched up instead, but it was not a long term solution.

Removing the dam altogether, as mentioned in the Part 1 article on Cape’s history, would be expensive. Without the dam, the millrace would dry up, leaving the creek bed exposed for deterioration. A solution would have to be made to not only protect the vegetation, but also to divert water into the main channel. Runoff, as well as reservoirs from The Woods apartments, currently drain into the millrace, causing another obstacle for ecological protection and flood prevention. Also, during high flows, the unfilled millrace would house the endangered fountain darter, and when the flow lowers, the fish will be trapped and often die in the near-dry channel.

Also, funding for removal might prove more difficult for disrupting an environment USFW is supposed to be protecting. Restoring or otherwise altering the dam to maintain the millrace would be more likely to draw grants for the project.

Protection of the environment is also what will give dam removal advocates an uphill battle. None of the permits that had been applied to in order to remove the dam have been approved. The city is again, essentially, at square one.

A repair, on the other hand, would not need as many approvals, would be more practical in terms of recreation, would continue to provide safe water runoff and maintain the habitat for our endangered species.

And since we’re at square one, perhaps this is an opportunity to rethink what the community really needs and wants from this project.

Read part 1 by Candice, The Past: A History Of Capes Dam